Mudsnails provide water quality indicators

February 28, 2018 - Adityarup “Rup” Chakravorty

A tiny snail could be a big help to researchers measuring water quality along the U.S. and Canadian Atlantic coast.

Eastern mudsnails live in coastal areas from Nova Scotia to Georgia. In many of these areas, human activities have brought large amounts of nitrogen to coastal habitats.

Nitrogen is an important nutrient, but high levels can severely affect aquatic ecosystems. For example, when large amounts of nitrogen are available, dense blooms of algae can form. These algal blooms use up a lot of oxygen. That can cause low-oxygen dead zones where other aquatic organisms have difficulty surviving.

In a recent study, researchers show that eastern mudsnails can serve as proxies for how much nitrogen is in an ecosystem. That knowledge is key to identifying and remedying ecosystems where water quality is compromised.

“This is perhaps the first study to highlight the use of these snails as water quality indicators,” says Elizabeth Watson, lead author of the study. “I think scientists will now be much more confident in applying this approach in areas across the Northeast.” Watson is a researcher at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia.

In this study, researchers measured levels of two different versions, or isotopes, of nitrogen in mudsnail tissues. “The proportions of heavier and lighter versions of nitrogen show how much nitrogen is available in that ecosystem,” says Watson. Higher levels of the heavier version in mudsnail tissues signal higher overall levels of nitrogen in the environment.

Researchers collected mudsnails from over 40 study sites. These sites were spread across Long Island, New York. They found that the heavier version of nitrogen was enriched in mudsnail tissue in several study sites.

“These sites were near areas with high population densities, or where land use is more urbanized,” says Watson. “We also had similar results from sampling sites next to wastewater treatment plant discharges.”

Some of the study sites are extremely nutrient-polluted, according to Watson. An example is areas that experienced the discharge of untreated sewage during heavy rains.

However, nitrogen pollution is also a concern in more pristine coastal areas, such as eastern Long Island and Barnegat Bay. In these areas, the goal is to detect and undo human impacts.

“We want to preserve coastal wildlife,” says Watson. “We also want to protect human activities, such as harvesting (fishing, clamming) and recreational opportunities.” Mudsnails could help researchers do that.

Mudsnails are convenient organisms to use as water quality indicators. They are small, usually less than an inch in length. They are abundant, with up to 1,500 mudsnails per square meter. “They are also pretty easy to catch,” Watson adds.

Mudsnails also live for a long time–over 50 years in some cases. Although water samples “reflect just one instant in time,” says Watson, a mudsnail sample reflects an entire lifespan. “By analyzing mudsnails, researchers can get an idea of conditions over a much broader period of time.”

Also, using mudsnails as indicators of water quality could engage local populations. According to Watson, citizen scientists and organizations can help collect and prepare mudsnails for isotopic analyses.

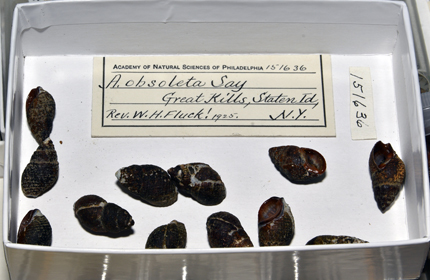

Watson is now trying to establish water quality baselines for New York and New Jersey based on analysis of older material. She is working with the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

“The academy has collections of mudsnails that are at least a hundred years old,” says Watson. “We can analyze recently-collected mudsnail shells and compare them with shells from a century ago.” That can help researchers detect how much nitrogen levels in coastal areas have changed over the last hundred years.

Watson’s research is published in Journal of Environmental Quality. The Zegar Family Foundation and the Pritchard Family Trust supported this research.